|

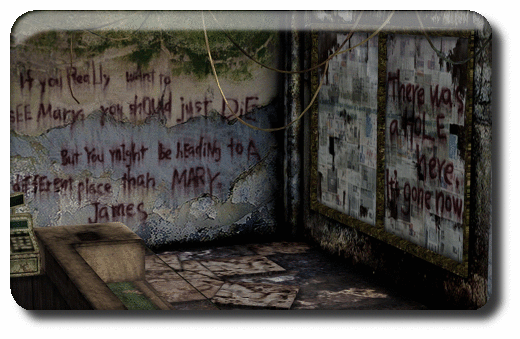

By the time a sequel to the ground-breaking original Silent Hill was announced, “Survival Horror” had become well established as a dominant genre within the video games industry; many, many attempting to ape the success and popularity of the Resident Evil and Silent Hill franchises with extremely limited succes. The core mechanics of “Survival Horror” became entrenched within video game culture and design: placing the player in a situation of escalating threat with limited ammunition and access to health items, punctuating the more Zelda-esque elements of exploring labyrinthine environments for keys, weapons and items etc with safe rooms, horror set pieces and expository encounters. Most followed in the same vein as earlier titles in the genre, the vast majority little more than derivative clones of one or both franchises, with little to distinguish them or genuinely horrify their intended audience. Owing largely to the genre's overnight success and market dominance, players soon became extremely familiar with its tropes and cliches, many of which, ironically, derive from the far older, more traditional media they reference (i.e. in Resident Evil's case, various horror and science fiction b-movies, whereas Silent Hill's influences are somewhat more abstruse and literary in nature). As a result, the games became escalating arms races: what could be done within the constraints of both the genre and comparatively limited technology to reinvent the experience and make the games distinct, novel experiences? Furthermore, the culture and audience for “Survival Horror” were developing as the games themselves were; those of us that were fourteen or fifteen when the original games were released were now approaching our early twenties, meaning that, not only were our appetites somewhat more sophisticated, but there were also far more “real life” pressures and constraints on our time. Therefore, any games that snared our attentions would have to be special indeed. To add to the sub-genre's woes, in this tumultuous era of video gaming's evolution, it found itself no longer the exclusive font of horror and disturbia in video games: The likes of Half Life, System Shock, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream...even Doom and its various derivatives were all evidence of an efflorescence of horror within video games, all highly distinct from one another, and appealing to tastes that were perhaps alienated by “Survival Horror's” escalating descent into formula. Resident Evil 3 and Silent Hill 2 took differing approaches to these problems: whereas Resident Evil 3 attempts to invigorate itself with fresh (un)life by introducing novel technical elements and game dynamics, Silent Hill 2, with its much longer development cycle and shift to the next generation of video games consoles, focuses instead on aesthetics, atmosphere and storytelling, resulting in what is still regarded by many as the high water mark not only for “Survival Horror,” but horror video gaming itself. Resident Evil 3 was always going to be at somewhat of a disadvantage, being released at the time it was, when so many of the franchise's original fans were simply moving on, growing up, focusing energies instead on building lives for themselves. Also, it was the classically difficult “second sequel” in a horror franchise, which, if one casts an eye over the various horror film franchises it draws inspiration from, is often the point of descent into mediocrity, if not outright disgrace. Not that Resident Evil 3 is a bad game at all; far from it. In fact, many cite Resi 3 as their favourite instalment in the franchise, and it's not difficult to see why: Reintroducing fan favourite from the first game, Jill Valentine, the game initially seems to have all of the familiar elements in play: locked camera angles, classic “Survival Horror” tank controls and inventory system...even the environment is familiar, as the game is set during the same time frame as Resident Evil 2, and utilises may of the same environments from that game. The new dynamic occurs in the form of Nemesis; a derivative of Resident Evil 2's Mr X; a seemingly invulnerable bio-weapon that is dropped into the play environment by agents of the Umbrella corporation with the pre-programmed mission of destroying all members of the S.T.A.R.S team, that have consistently foiled the corporation's agenda in previous instalments. Nemesis is a highly unusual factor in the game, in that he turns up at various random and pre-determined instances, though, until the player has finished the game through, they will never know where he might or might not occur. The sense of being hunted throughout the game lends proceedings an air of consistent tension that previous titles (arguably) didn't boast, which explodes into lunatic panic whenever he is encountered, often resulting in lethal mistakes. Another novelty is the almost unheard of element of choice within the narrative; whilst previous games allowed the player some very limited degree of player choice when it came to the order in which certain events occurred, for the most part, they ran on rails, directing the player down pre-determined paths via use of locked doors, blocked passageways etc. Nemesis introduces this factor through the encounters with the eponymous murder-machine itself; when Nemesis occurs in any environment, the action momentarily slows down, allowing the player to make the choice of either fleeing or fighting, both of which drastically alter the outcome of the game and its narrative (characters live or die depending on what “pattern” of choices you make. Even some key encounters are significantly altered). This not only introduces a new onus for the player, but also enhances the horror with a level of raw panic that arguably wasn't present in previous titles. Furthermore, being one of the very last significant titles released on the original Playstation, the game is perhaps the most gorgeous looking of any of them, pushing that system to its absolute limits with dynamic and diverse character models, fantastic pre-rendered backgrounds and some truly stunning new monsters to get to grips with. And it's at this point that I must make an admission that may earn me more than my fair share of ire: I don't like Resident Evil 3. Of the original titles, it was the first I started playing and never finished. Looking back, this was not primarily due to any failing on behalf of the game itself, though there are one or two that still gripe to this day: First of all, whilst the concept of Nemesis is excellent, his design is...perhaps my least favourite of the big “end of game” monsters that the series has boasted: the original game's Tyrant, Resident Evil 2's William Birkin and Mr.X all boasted a certain consistency of design and clear influence from works such as John Carpenter's The Thing and H.R. Giger's paintings. Nemsis doesn't do it for me; the design, if anything, comes off as a little...goofy; a factor that dilutes his presence within the game, especially when you realise that, in most of the encounters with him, he's actually fairly easy to deal with. Then there's the atmosphere, which, unlike previous Resi titles is somewhat diluted in favour of ladling on action set pieces (a shift in theme and focus that would only escalate as the franchise aged). Resident Evil 1 and 2 had little choice but to utilise raw atmosphere to conceal or divert from their technical short comings: the comparative sophistication of Resident Evil 3 means that a similar degree of subtlety and inspiration isn't present; whilst the environments are gorgeous, far more interactive and dynamic, they simply lack the feeling and gravitas of those in the first two titles, acting more as arenas for action set pieces than means of evoking atmosphere. But, beyond any technical faults the game might or might not exhibit (and I fully accept that it's the most technially accomplished and consistent of the first three games), my disregard for the title primarily stems from my own status: by that point, I, like so many, had become extremely familiar with the tropes and cliches of “Survival Horror,” such that, they simply lacked purchase any longer. Also, we had started to experience other forms of horror in video games, most notably on my part via the likes of System Shock and its sequel, which, much as I adore the first two Resident Evil games, is leagues and bounds beyond them in terms of sophistication. Resident Evil 3 marked a cultural transition, for me and many others; the saturation of “Survival Horror,” and the necessary shift in the work that comprised it, if it was to survive: Silent Hill 2 occurred during the early days of the much loved Playstation 2 system; a platform widely praised for the variety and innovation of the titles it boasted, amongst which Silent Hill 2 has a tendency to top charts. Whereas Resident Evil's first two sequels felt more like expansions or adaptations of the original game, only altering its core mechanics and structure in the subtlest of ways, Silent Hill 2's longer development cycle meant that it was a quantum leap from the original; the title that firmly cemented its franchise as a heavy hitter not only in horror, but in video gaming as a narrative medium. Resi 3 attempted to inject new (and synthetic) life into its parent franchise by introducing a smattering of new gimmicks and technical elements, whereas Silent Hill 2 takes a more mature, considered approach; its mechanics not much removed from those of the original or, indeed, the original Resident Evil, but distinguishing itself in a more subtle, artistic manner: by providing gamers with concepts, imagery and stories the like of which we'd never seen before. If the original Resident Evil was a bomb shell to our assumptions of what video games were capable of, Silent Hill 2 was the apocalypse that resulted: With “Survival Horror” firmly established as an entrenched and exceedingly familiar genre by the point of its publication, the game doesn't attempt to blind-side or surprise with technical shifts or innovations. Rather, it has a keen and abiding agenda to disturb and distress, beyond the pulpy, b-movie shocks of the Resident Evil series, attempting to worm its way beneath the player's skin, into our souls, to make us feel somehow soiled for being in contact with it. The setting and situation are simultaneously similar to those of the original game yet significantly removed: foregoing the original's characters in favour of an entirely new cast, the game follows James Sunderland, as opposed to Harry Mason, who arrives in Silent Hill by intention rather than accident, ostensibly in search of his wife, Mary, with whom he has memories of sharing holidays in the town. The only problem is that Mary is dead, having succumbed to an undisclosed illness at some point in James's recent past. A cryptic letter that seems to be from Mary adds a further layer of perplexity: is she somehow alive, is James entirely sane? The game immediately distinguishes itself as being slower paced than the original, building a creeping tension and sense of spiritual dread before unleashing its strangeness and absurdity: On his way into the town, James encounters characters who talk in a strange, dreaming, almost delirious manner, emphasised by what might be the poor translation from its original Japanese: the entire effect is of being lost in a nightmare, which operates on its own peculiar logic, and in which characters act and react on bizarre, idiosyncratic ways. James himself is an odd character; gruff, taciturn, dishevelled and clearly in a state of distress, it isn't long before the player starts to get the impression that all isn't well with him; that they may perhaps be in control of a man with more demons than even Silent Hill can reflect. Whilst the original game hinted at Silent Hill being a psychosomatic environment (i.e. one that responds and reshapes itself in accordance with the psycological states of those that wander there), Silent Hill 2 cements that concept: all of the various creatures and environments players encounter in the game are uniquely disturbing; a far cry from the zombies, science fiction beasties and body-horror monstrosities of the Resident Evil series, these creatures are far more redolent of fevered nightmares, drug-induced hallucinations, the dredgings and unlovely births of a diseased sub-conscious. Each and every one of them reflects some element of either James's own tortured psyche or those of the other characters he encounters, lost in Silent Hill. From the twisted, mutilated -yet distressingly sexualised- nurses that derive from his anxieities over his wife's illness, but also his burgeoning sexual frustration, to the shambling, “straight-jacket” like mounds of flesh that are directionless and constrained, reflecting his sense of hopelessness, his escalating loss of control, every aspect of the game is tailored to resonate with symbolism, meaning that, unlike its counterparts in the Resi series, it functions as far more than a mere game: Demanding player engagement in a manner that few -if any- horror games of the era did in order to be fully appreciated, it functioned more like an example of surreal art or literature; an animated Francis Bacon or Goya painting, the player -as well as James himself- projecting their own sublimated concerns and distresses upon its imagery, the game worming its way far, far deeper than any superficial responses of survivalist dread or disgust, creating a more intimate and unsettling experience that was largely unheard of amongst video games of the era. For perhaps the first time, video gamers were treated like adults by their medium of choice; as considered, complex and engaged entities that didn't require immediate or peurile gratification; that could appreciate subtlety, nuance and intimation in the manner of the audiences for literature or cinema. Whilst many of us didn't consciously acknowledge or appreciate it at the time, the sense of frisson that Silent Hill 2 created through its characters, its complex and ambiguous relationships, its hideous and nhilistic metaphysics, has continued to resonate down the years, such that a casual search of the interwebz will still, still turn up myriad articles and essays attempting to unpick its symbolism, to interpret what certain situations and images might be attempting to relay. The game is a masterwork of symbolic ambiguity, not spoonfeeding the player with wearisome and debilitating exposition or synthetic interpretations of events, but leaving it almost exclusively in their laps, as their responsibility to interpret. In that, the game acts as a kind of Rorschach ink blott test; like Silent Hill itself, it provides only what you bring to it; the horror deeply personal, intimate and violating, more in the vein of a Clive Barker novel or David Lynch film than a b-movie bit of zombie schlock. Also, the game is sufficiently sophisticated to make the player character a source of that ambiguity; whereas the vast majority of player avatars in video games are morally absolute, heroic characters, James Sunderland is gradually revealed as being a broken, tormented, not entirely pleasant man, whose actions are what have stirred Silent Hill to its current state of activity: tortured by his feelings and actions towards his ailing wife, he must confront the physical manifestations of those sins, including arguably the most iconic entity in the game's history: The immortal homonculus, “Pyramid Head.” Perhaps the most disturbing entity ever introduced into Silent Hill, “Pyramid Head” is a uniquely violent and threatening entity that, far from merely attempting to harm those around it, exhibits proclivities that are far more complex and horrific: when first encountered, it is glimpsed from within a sealed closet (an echo of childhood nightmare scenarios), seeming to graphically rape one of the more feminine monstrosities from the game. When James finally encounters the creature face to face, he finds it slow, ponderous and patient; an immortal butcher that cannot be slowed or stopped. It isn't until James finally allows himself to confront what he has done, to feel and exorcise his guilt, that “Pyramid Head” commits suicide, allowing him to progress to the final encounter and the ultimate revelation of what actually happened to James's wife. The consistent symbolism throughout the game, the fact that many enemies don't have to be fought and defeated so much as escaped, exorcised or tackled in a more oblique manner, makes for a vividly different experience from the ailing Resident Evil series; an enduring sense of disturbance that has elevated Silent Hill to such heights that it remains at the top of many gamer's favourite horror games of all time. For those of us that had grown up with the medium; who had seen the efflorescence of “Survival Horror” in its most recent evolutions, Silent Hill 2 marked the point at which we began to realise that video games were capable of more; that they do not need to be so codified or simplistic in what they provide; that they can be appreciated to the same -if not deeper- degrees than more traditional formats. The game spurred a sudden explosion in “artistic” horror video games; titles that didn't simply intend to scare or repulse, but to violate the player; to engage them on deeper, more intimate levels, and in ways that would give rise to entirely new forms of horror in generations to come. FICTION REVIEW: INTERLUDES FROM MELANCHOLY FALLS VOL. 1 BY JEFF HEIMBUCH

|

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed