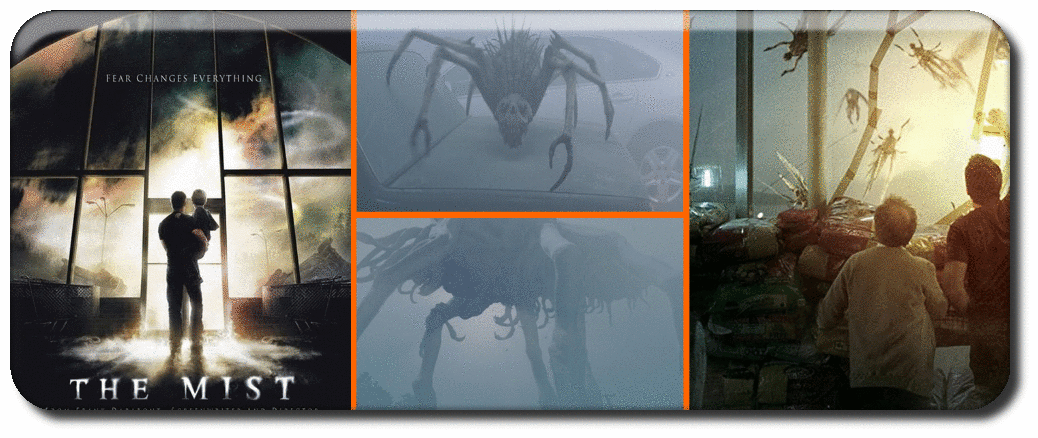

It is an empty elegy; profound in its redundancy, epic in its vacuity. Have you ever wondered what the elegy for a dying world would sound like? What must've echoed throughout Heaven following the war that split it in two, the ultimate failure of all creation? That's pretty much what you get with the soundtrack to Frank Darabont's big-screen adaptation of Stephen King's Lovecraftian, apocalyptic novella, The Mist. Darabont is the perfect director to adapt King's material; not only does he understand it on an intimate level, he also understands when it needs to be reworked, altered or re-imagined for the format of cinema. In The Mist, he takes the story's Lovecraftian horror and suffuses it with painfully self-destructive, human tribal stupidity; the inclination on behalf of desperate humanity to try anything, any means, to save itself from impending doom, even if it means returning to the old days of blood-sacrifice and scapegoating. Taking that misanthropy and essential nihilism as its thesis, the cinema adaptation of The Mist is an exercise in excoriatingly human horror. Whilst the extra-dimensional monsters that descend on the small, mid-western town that is the story's setting are treated in the manner of some arbitrary, apocalyptic disaster, the true horror derives from the desperate, foolish, terrified cluster of human beings barricaded in the local supermarket (a nice thematic nod to George A. Romero's Dawn of the Dead). As one of the key characters notes, it takes less than three days before they start turning on one another in scapegoating violence, grimly inspired by the sickest, most deranged and depraved amongst them, who they turn to as a beacon of certainty -however lunatic- as the world around them falls apart. The soundtrack, for the most part, is minimalist and incidental; a perfectly functional horror-film score that serves to emphasise tension, compound the horror occurring both inside and out. It isn't until the apocalyptic scale of the event becomes apparent that the score swells and transforms, becoming a celestial mourning for lost creation with The Host of Seraphim: Beginning with an atonal, hymn-like chord of organ music, the piece erupts into vocal bravura that has all of the resonance of a Mother goddess lamenting the murder of her children. It is the very essence of despair and loss; the cosmos weeping for humanity where there are no angels left to do so. The event that has been unleashed on Earth -which may or may not be the result of human military science tampering in extra-dimensional technology- has much wider significance for the universe and reality as a whole: There's no saying, by the film's end, if the event can be reversed or if the disease-like invasion of another reality, entirely antithetical to our own, will continue to spread and spread until it subsumes or collapses creation itself. Like Lovecraft before him (whose work is an obvious thematic inspiration), King revels in emphasising the cosmic insignificance of humanity, and exposing how what we consider most sacred in our lives is ultimately ephemeral nothing, swept away by accidents and vicissitudes of reality that we can barely perceive, much less comprehend or predict. All of human history is undone within a matter of days here, swept away by an alien reality that seems entirely animal; an extra-dimensional wilderness that, the story even dares suggest, might be better than what we've created with our endless war, pollution, man-made extinctions etc. Unlike in the vast majority of King's work, there is no salvation here; nothing that can save even the most innocent of us. Reality does not care; there is no god, no angels (or, if there ever were, they are impotent or long, long dead). This lends the film's score a note of hideous irony; the eponymous “Host of Seraphim” might mourn, but they either did nothing to prevent the tragedy or were impotent in the face of it. In point of fact, faith itself is painted as powerfully negative throughout; a source of enshrined neurosis that leads to nothing less than scapegoating murder and the lionisation of lunatics. Those that sing for dying creation here do so in the full knowledge that there's no one and nothing to hear, no one and nothing that will mark the passage of humanity or the world itself. It is an empty elegy; profound in its redundancy, epic in its vacuity. And it is one of the most soul-shudderingly beautiful soundtracks in horror cinema history. CHECK OUT TODAY'S OTHER ARTICLES BELOW |

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed