|

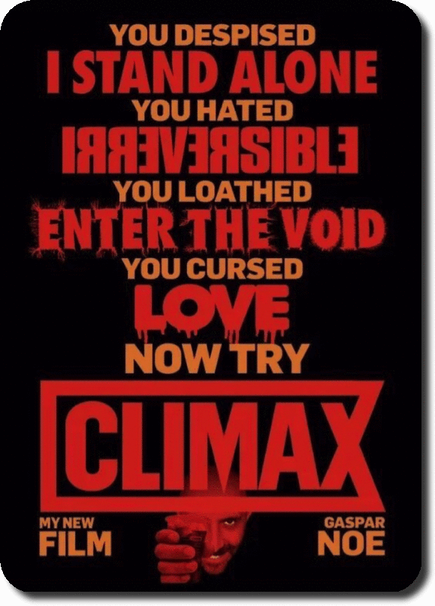

Two observations; Observation one; Some things are best experienced just the once. At Universal Studios in Florida, there's a Jurassic Park Ride. It's promoted as a lovely sedate cruise through some of the various impressive dinosaur exhibits there but, within minutes of it starting, everything went horribly wrong. Turned out that some Velociraptors and a T. Rex had escaped from their paddocks and were raising hell. The staff assured us that this wouldn't affect our experience – but this was at best, hopelessly naïve. Criminally so, in hindsight. It made our experience terrifying. Not only did we have to dangerously traverse a section of the park crawling with the vicious clawed bastards, but we only narrowly escaped our boat being devoured by the gaping maw of a slavering Tyrannosaurus Rex. What should have been a dream holiday was somewhat tainted by this horrifying experience. Naively, we went on the same ride three days later. And, bugger me, if the same mishaps didn't occur again. Shoddy health and safety at best, and this in a park with thousands of visitors a day. Appalling negligence. Observation two; "Style over Substance," is a commonly used phrase in critique, an indication that whereas something may be visually or orally striking, there isn't a great deal of depth or meaning to it. It's designed as a barb, a word as equally weighted as "pretentious" to pour scorn on something that isn't deemed to have the necessary highbrow/lowbrow values or qualities to achieve some invisible abstracted standard. I'll give away my age here, but in the early-to-mid-eighties only one type of music existed. It was made solely by men, a few of whom were guitar virtuosos called Mark. Some wore headbands, T-shirts only came in white, and all its various (typically middle-age) idols wore single or double – and in some rare ostentatious cases, triple denim - and keyboards were designed to be stabbed at viciously or worn around the neck. At least only one type of music existed to me. These fretted warriors sang stoic ballads of Brothers in Arms, former capitals of Brazil, Mad Worlds and of money for nothing (and chicks for free) as well as Bricks in Walls (parts 1 and 2). The insidious agency of Stock, Aitken and Waterman did their damned best to intrude on my little world, but my sophisticated teen ears had become well trained in filtering them out. I was a musical snob. I listened to one type of music, although was clearly refined and sophisticated enough to let that warp and shift – AOR become Soft Metal, Soft Metal hardened to Heavy Metal, Heavy Metal slunk into the talcum-powdered trench coats of Goth, Goth plunged screaming (in German) into Industrial. Madchester passed me by, as did the New Wave of the New Wave of the New Wave (or whatever bloody wave we were up to by now). The Blur versus Oasis Wars might well have been taking place in the Middle East, such was their relevance to me. I probably used the phrase 'style over substance' to define the types of music I refused to listen to on more than one occasion, never really understanding quite what I was saying. It just sounded good, like repetitive overuse of the gag; “Condescending. It means ‘talk down to’.” As I grow older, the phrase "Style over Substance" holds less and less meaning. The esoteric nature of it fades as it loses power. My musical tastes were forced to broaden, faced with an onslaught of songs from different genres that were simply too good to ignore, and there comes a time when you realise when there is a perfectly valid place for beauty for beauties sake, no hidden depths, no passive subtext. I'm very aware that – in topical terms – I'm quite late to come to Climax (no pun intended). Expect cutting edge articles on Dead of Night (1945) very shortly. However, having seen it – or, more appropriately, experienced Climax – I feel compelled to write about it. Climax is a film that I have watched and have watched from start to end. I didn't know what to say when it had finished, other than I felt exhausted and needed a very long sleep. Most of my thoughts were occupied with it the next morning at work, and at lunch I rang my wife and told her this. She'd been singing the film's praises for several months, and had been nagging – no, encouraging me to watch it. "See, I told you," she said, justifiably smugly. Many of my thoughts have been occupied with it in the days that passed. Climax (2018) opens to whiteness, an aerial shot of a barely dressed woman staggering through the snow. Dogs bark in the distance, almost drowning out her anguished cries of distress. She collapses in the snow, writhing arms forming a makeshift snow angel. She crawls on, before collapsing. Is that blood underneath her? The camera, unconcerned by her still form, moves on. End credits roll. Okay, so that just happened. A white-noise flecked VHS video tape plays on a television, each character – a dancer from a troupe – is given a name, and a short soundbite to describe themselves. Each describes their dreams, ambitions and aspirations, they elaborate their fears and the reasons that they dance. The screen goes black, Supernature, the awesome 1977 track by Cerrone begins to play. The troupe emerges, like regimented troops to the battlefield, onto the dancefloor. We're then treated to a magnificent few minutes of cinema as the cast simply dance. The scene is part choreographed/part improvised, and I honestly don't think I breathed during the entire sequence. It's utterly joyous – dancers at the height of their skills and the peaks of their careers, utterly lost in the moment. It's the Winter of 1996, and we’re witnessing a French dance troupe in an abandoned school having a tour after-party. One thing you should not expect from Climax is characterisation. Some of the characters are so poorly defined that they're barely even archetypes – some of them barely delineated more than by the fact that we know their actual or stage names. It's interesting that we learn a lot about many of the characters simply from their dancing – we learn who the confident and flamboyant ones are, who the more retiring ones are. We learn hints through eavesdropping in conversations taking place around the party. As with any large group of people thrust together for any prolonged period, there's a complex web of relationships of which we pick up only hints. There are burgeoning romances, and a lot of horny dancers who want romance. Improvised vignettes between groups of the characters reveals a little more about each of them – a lot of it revealing that a lot of the male dancers shouldn't be allowed anywhere near women, but on the whole, we're just witnessing a party in which people are becoming increasingly more stoned and drunk. We have lesbians, gays who lust after straights, junkies, protective mothers forced out of a dance career through their decision to have a child, jealousy… And then the movie hits the halfway mark, and we get the opening credits. With hindsight, it's a kind of warning – you've had your opening and closing credits, best leave now, if you know what's good for you… Somebody has spiked the party Sangria with copious amounts of LSD, and it's starting to kick in… I cannot of course, as a responsible adult, condone drug use – but Climax, much like the notorious Lysergic Acid Diethylamide itself, is something better experienced than talked about, so this will be relatively spoiler-light. It kicks off with paranoia; fingers being pointed as to which irresponsible fucker drugged the party punch. With tempers flaring and moral judgements clouded by the heady stupor of powerful hallucinogens, violence ensues. Fights break out, and one dancer – Muslim and non-drinker, so clearly guilty – is thrown out and abandoned to the deluge of Winter – the first to be cast out of hell. A lot of the ensuing tale takes place in the rooms set off the main dance floor, including the generator room, where a hysterical mother is forced to lock her screaming child up for his own safety. As a brilliant plot device, Noé keeps bringing us back from the rooms on the periphery to the central dance floor. With every revisit, it's plunged deeper into chaos, the already tattered membrane between reality and insanity that little bit more frayed with each encounter. The lighting and soundtrack change accordingly, an effective visual and audio cue keeping track of quite how far down into Hell we've been dragged. (Special mention here needs to go to the soundtrack, which is something that's occupied much of my Spotify habit since I first saw Climax. Burn Baby Burn, Disco Infernal – it's the playlist for the party from Hell. Aphex Twin's Windowlicker nestles neatly next to classic Giorgio Moroder, M/A/R/R/S' Pump Up the Volume shares a list with a sublime instrumental version of the Rolling Stone's Angie - and it's a work of absolute perfection). You begin to dread each revisit to the dance floor, the director almost holding it over you as a threat. As the character you're following drunkenly staggers back into that central chamber, a strobe lit Stygia, you fear for what is coming next. Whereas this at-times jaded horror fan thought he'd seen it all, much like that bit at the end of Zahner’s Bone Tomahawk (2015) – the thought of which just caused at least one reader to wince and close their legs – I wasn't quite prepared for the end. It's not particular gory or scary, but the closing scenes of Climax will stick with me for some time. Weird angles and lingering shots that went on for just-that-little-bit-too-long made me feel quite queasy and I was wanting the film to end. But that's not a criticism; that's how you should feel. It's an experience. A thrill-ride. An experimental tour-de-force by a director who has made a deliberate career out of controversy and shock - Enter the Void (2019) and Irréversible (2002). You will take nothing away from it, no deeper meanings or hidden profundity. There are no lessons learned, nothing gleaned other than the fact you've just watched a group of people succumb to madness – and not all of them came out of it the same, or in some cases, alive. Style over substance, whatever. But sometimes you just crave a Pot Noodle rather than Filet Mignon, italicized for extra pretension. And, to stretch that fast food metaphor one micrometre too far, Climax certainly stuck in my gut. It’s terrific. But I don't need to watch it again. I learned my lesson at Universal Studios. Here be Velociraptors. Further Reading/Viewing Criterion regularly do videos in which they invite actors and directors to pick a choice of films from the shelves in their warehouse; Noé's choices are particularly interesting and enlightening, and can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_2R7T4-78E Even if you don't watch the film, you owe it to yourself to watch the opening dance sequence by clicking on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hwkacrln26o&t=57s. Honestly. You'll thank me. About the Author |

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed